Un estudio del ICTA-UAB y del Departamento de Sanidad y Anatomía Animales demuestra que las principales especies que cazan los indígenas de la selva amazónica de Perú ingieren agua y tierra contaminadas por hidrocarburos y metales pesados.

05/03/2018

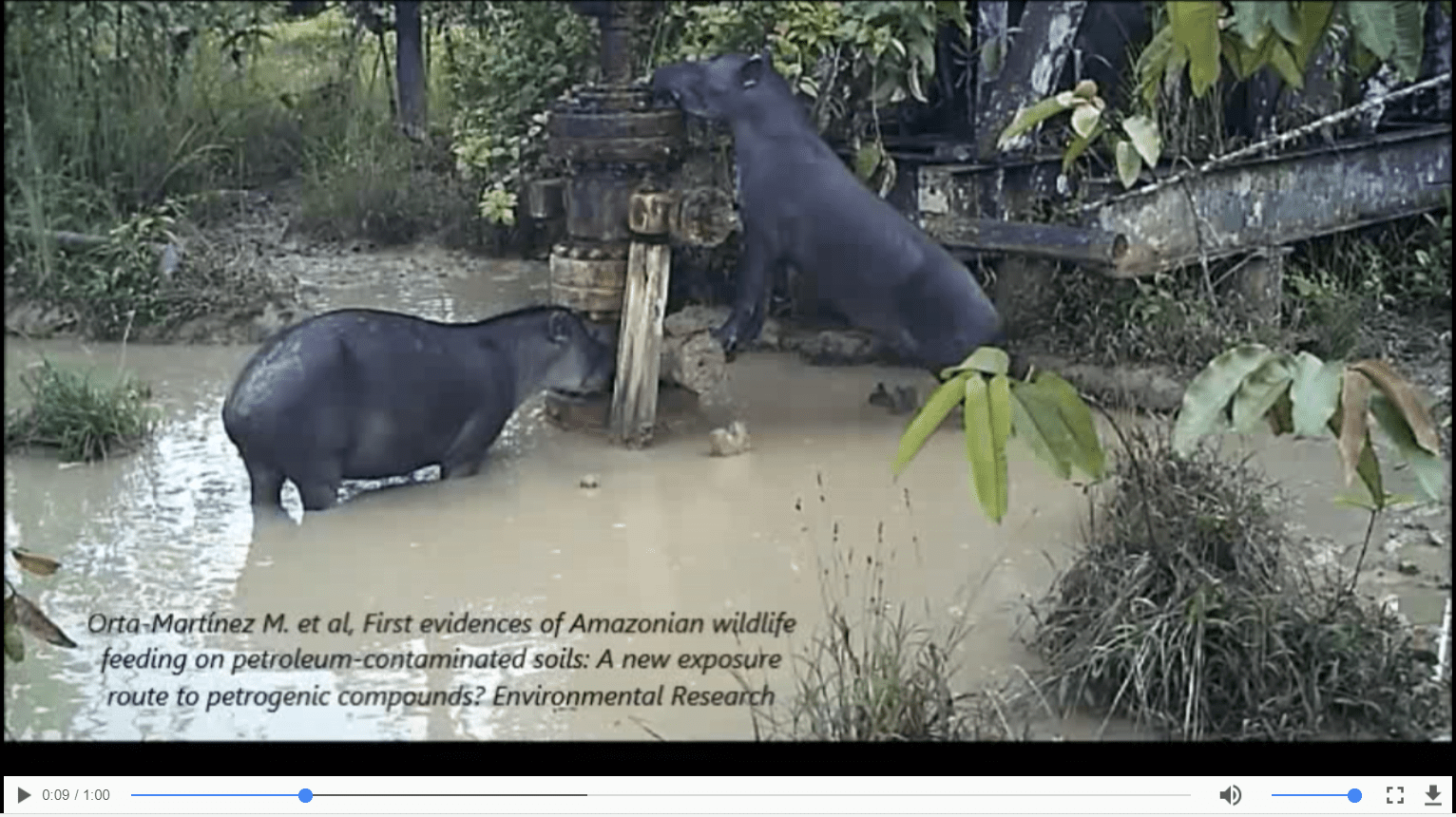

La fauna salvaje, que cazan las poblaciones indígenas del Amazonas, ingiere agua y tierras contaminadas por la industria petrolera, según indica una investigación del Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (ICTA-UAB), el Departamento de Sanitat i Anatomia Animals de la UAB, el Instituto de Salud Global de Barcelona (ISGlobal) y el International Institute of Social Studies (ISS-EUR). El estudio, que muestra por primera vez imágenes de cómo los animales acuden a beber agua e ingerir tierras (geofagia) contaminada por vertidos, o directamente a los pozos petroleros, alerta del riesgo que este hecho supone para la salud de las poblaciones que dependen de la caza para su subsistencia.

La investigación, publicada en la revista Environmental Research, forma parte de un amplio proyecto científico desarrollado por el ICTA-UAB y liderado por el Dr. Martí Orta-Martínez desde hace más de una década que analiza los preocupantes niveles de contaminación por petróleo existentes en una zona remota de la Amazonía peruana próxima a la frontera con Ecuador. Los científicos habían demostrado previamente cómo la actividad petrolera lleva cuatro décadas contaminando de manera generalizadas las tierras y las cabeceras de los ríos no sólo a través de los vertidos accidentales de petróleo sino, en mayor medida, al habitual vertido de las aguas de producción, extraídas de los yacimientos junto con el petróleo. Las aguas de producción petroleras tienen altas concentraciones de sales y metales pesados como plomo, cadmio, cromo o bario e hidrocarburos. Esta contaminación, que afecta a los ríos, suelos y sedimentos, extendiéndose hasta 3000 kilómetros aguas abajo del río Amazonas, es bioacumulable, pudiendo poner en riesgo la salud de peces, animales y las personas que se alimentan de la caza y pesca.

La instalación de cámaras trampa permitió registrar principalmente imágenes de cuatro especies de fauna salvaje (tapires, pacas, pecaríes y venados rojos), las más importantes en la dieta de las comunidades indígenas de la región ya que suponen entre el 47 y el 67% del total de la carne que consumen. Estos mamíferos, residentes en ecosistemas pobres en sales como los amazónicos, suelen compensar esta carencia dietética acudiendo a afloramientos minerales naturales para ingerir tierra (colpas o salitrales). Sin embargo, los animales visitan ahora los vertidos de petróleo atraídos por la elevada salinidad de las aguas de producción petroleras. Además, otras especies de fauna salvaje que se encuentran en peligro de extinción han sido observadas realizando el mismo comportamiento.

El siguiente es el material complementario relacionado con este artículo Vídeo

El hallazgo podría tener relación con los elevados niveles de plomo y cadmio detectados en la sangre de los 45.000 habitantes de las cinco etnias indígenas de la zona. Según el Ministerio de Salud del Perú, el 98.6% y el 66.2% de los niños indígenas del área excedieron los límites aceptables para el cadmio y el plomo en sangre, así como el 99.2% y el 79.2% de los adultos.

Esta área de selva amazónica fue declarara por el gobierno peruano en emergencia ambiental en 2013 y en emergencia sanitaria en 2014, pero todavía no existen registros locales de morbilidad ni mortalidad. Sin embargo, los científicos recuerdan que “estos compuestos son neurotóxicos y cancerígenos”.

Proyecto de participación ciudadana

En el marco de este estudio, el ICTA-UAB y el Dpto. de Sanidad y Anatomía Animales de la UAB, han puesto en marcha un proyecto de participación ciudadana que pretende, respaldándose en el conocimiento colaborativo, identificar otras especies que puedan aparecer en las más de 8.000 grabaciones de vídeo trampas que se llevaron a cabo en la zona de Loreto (Perú) durante 500 días.

Mediante la creación de una plataforma digital interactiva en inglés y español, se quieren identificar todas las especies amazónicas que aparecen ingiriendo aguas y tierras contaminadas con contaminantes petrógenicos, así como analizar su conducta. La plataforma ‘AmazonOil’, implementada con una subvención de la Fundación BBVA, cuenta con el apoyo de las asociaciones indígenas de la zona FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, OPIKAFPE y ACODECOSPAT. La versión definitiva de la plataforma de ciencia ciudadana podrá consultarse a partir del próximo 28 de marzo en la dirección web https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/marcartro/amazonoil

Artículo de referencia:

Orta-Martínez M., Rosell-Melé A., Cartró-Sabaté M., O’Callaghan-Gordo C., Moraleda-Cibrián N., Mayor P. First evidences of Amazonian wildlife feeding on petroleum-contaminated soils: A new exposure route to petrogenic compounds? Environmental Research. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.009

————-

Amazon’s indigenous people hunt animals feeding in areas contaminated by oil spills

. A study by the ICTA-UAB and the UAB Department of Animal Health and Anatomy demonstrates that the main species hunted by the indigenous popoulations of the Peruvian Amazon ingest water and soil contaminated with hidrocarbons and heavy metals.

. The project has created a citizen science platform in which citizens can view videos recorded in contaminated areas of the Amazon so as to be able to recognise the affected species and their behaviours.

The wild animals hunted by the indigenous people of the Amazon rainforest drink water and eat soil which is contaminated by the oil extraction industry, according to a research by the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (ICTA-UAB), the UAB Department of Animal Health and Anatomy, the Institute of Global Health of Barcelona (ISGlobal), and the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS-EUR). The research, which for the first time reveals images of how the animals drink water and eat soil (geophagy) contaminated by oil spills or directly by the oil wells, alerts of the risk this represents for the health of the populations hunting these animals for food.

The research, published in Environmental Research, forms part of a broader scientific project developed by the ICTA-UAB and led by Dr Martí Orta-Martínez for more than a decade now, dedicated to analysing the alarming levels of oil contamination existing in remote areas of the Peruvian Amazon near the border with Ecuador. In previous studies, scientists demonstrated how oil extraction activities conducted in the past four decades have in general contaminated the soil and headwaters of the rivers not only through accidental spills, but also to a large extent by the discharge of produced waters extracted together with the oil. These produced waters contain high concentrations of salts and heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, chromium, barium and hydrocarbons. The contamination, which affects rivers, sediments and soil, spreads throughout 3,000 kilometres of the Amazon river and is bioaccumulative, putting at risk the health of fish, animals and the people who eat these animals.

The installation of camera traps allowed the recording of images of mainly four wildlife species (tapirs, pacas, peccaries and red deer), the most important species in the diet of the region’s indigenous communities, representing between 47% and 67% of their total meat consumption. These mammals, residents of an ecosystem poor in salt as is the Amazon, commonly supplement their diets with surface minerals by eating the soil. However, they have now been seen near the oil extraction sites, attracted by the high salinity of the produced water. The same behaviour was also observed among endangered species.

The discovery could be related to the high levels of lead and cadmium detected in the blood of 45,000 inhabitants of five indigenous ethnic groups of the region. According to Peru’s Ministry for Health, 98.6% and 66.2% of the area’s indigenous children surpassed all acceptable limits of cadmium and lead in blood, as did 99.2% and 79.2% of adults.

The Peruvian authorities declared this area of the Amazon rainforest an environmental emergency in 2013 and a health emergency in 2014, but there are still no local registries of morbidity or mortality. Nevertheless, scientists remind authorities that «these compounds are neurotoxic and carcinogenic».

Citizen Participation Project

As part of the study, the ICTA-UAB and the UAB Department of Animal Health and Anatomy launched a citizen participation project based on collaborative recognition which aims to identify other possible species appearing in the more than 8,000 camera trap recordings taken in the region of Loreto, Peru, during approximately 500 days.

Through the creation of an interactive online platform in English and Spanish scientists aim to identify all of the Amazon species seen consuming petrolium-contaminated water and soil, as well as analyse their behaviour. The “AmazonOil” platform, launched thanks to funding by the BBVA Foundation, includes the support of the region’s indigenous associations FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, OPIKAFPE and ACODECOSPAT. The final version of the citizen science platform will be available starting on 28 March at https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/marcartro/amazonoil.

Original article:

Orta-Martínez M., Rosell-Melé A., Cartró-Sabaté M., O’Callaghan-Gordo C., Moraleda-Cibrián N., Mayor P. “First evidences of Amazonian wildlife feeding on petroleum-contaminated soils: A new exposure route to petrogenic compounds?” Environmental Research. 2017